The Whanganui Chapter

The Whanganui Chapter

by Neeta Lind (Diné), Director of Community, Daily Kos

ABOUT THIS SERIES: In 2018 Movement Rights led a delegation of Indigenous and Rights of Nature Advocates from Turtle Island to New Zealand (Aotearoa) to share experiences and learn from the Maori iwi (tribes) who have recognized legal personhood for the protection of their sacred traditional lands. The land and waters are their spiritual ancestors—inseparable from their own identities. Over 10 days we visited with leaders from the Whanganui and Tuhoe iwi, Crown officials, lawyers involved in the Whanganui and the Te Urewera Agreements and Maori scholars who shared the legacy of Maori colonization. For many of us, this journey was among the most moving experiences of our lives. Delegates were asked to share their reflections as part of this series and in a newly released video of this journey. To our amazing guides and hosts, Hinewirangi Kohu Morgan and her team including Jo, Patrick, Te Awhiahua, Aniwa, Te Aho; and to the Maori and others who generously welcomed and opened their hearts to us, kia ora.

We left the lovely oceanside town of Whakatane the morning of April 27th for the five-hour drive across the country to Whanganui, home of the River People. The collective name for all of the iwi there is Ngāti Hau of which there were about 13,500 people in 2013.

We left the lovely oceanside town of Whakatane the morning of April 27th for the five-hour drive across the country to Whanganui, home of the River People. The collective name for all of the iwi there is Ngāti Hau of which there were about 13,500 people in 2013.

The tribes of Whanganui take their name, their spirit and their strength from the great river which flows from the mountains of the central North Island to the sea. For centuries the people have travelled the Whanganui River by canoe, caught eels in it, built villages on its banks, and fought over it. The people say, ‘Ko au te awa. Ko te awa ko au’ (I am the river. The river is me).

Europeans invaded Whanganui in 1840 and forced Christian religions on the Ngāti Hau. Inevitable conflicts occurred over land and resources and even caused in-fighting among the Ngāti Hau iwi resulting in a tragic battle in 1864. Riverboat tourism upset the Māori cultural fishing and harvesting practices. Modern industries polluted the river. Colonizers used the river for trash and sewage dumps.

The Whanganui River people had to fight for their river rights and in 1995 they occupied Pākaitore/Moutoa Gardens for 79 days in defense. It was the location of the 1864 bloody battle mentioned above.

In 2014, the Ruruku Whakatupua, the Whanganui River Deed of Settlement, was signed after 140 years of conflict with the Crown Government and was finalized in Parliament in 2017.

This settlement is in two parts:

Te Mana o Te Awa Tupua. This provides for the establishment of Te Pā Auroa nā Te Awa Tupua, a new legal framework to recognise the Whanganui River as a ‘legal person’. The Crown-owned parts of the bed of the Whanganui River and its tributaries will be vested in Te Awa Tupua.

Te Mana o Te Iwi o Whanganui. This provides financial redress of approximately $115 million, including $30 million towards Te Korotete, a fund to support the health and wellbeing of Te Awa Tupua.

The Whanganui River is considered an ancestor by the River People and with this settlement now has the same rights as a human being. The river now has the same protection as an individual, a protection from harm and abuse. Gerrard Albert, the lead negotiator for the Whanganui iwi said at the time:

“We have fought to find an approximation in law so that all others can understand that from our perspective treating the river as a living entity is the correct way to approach it, as in indivisible whole, instead of the traditional model for the last 100 years of treating it from a perspective of ownership and management.”

Chris Finlayson, the minister for the Treaty of Waitangi negotiations, said the decision brought the longest-running litigation in New Zealand’s history to an end. “Te Awa Tupua will have its own legal identity with all the corresponding rights, duties and liabilities of a legal person,” said Finlayson in a statement. “The approach of granting legal personality to a river is unique … it responds to the view of the iwi of the Whanganui river which has long recognised Te Awa Tupua through its traditions, customs and practice.”

A precedent has now been set for other Indigenous cultures to achieve their worldview that we are guardians of the earth and it is our responsibility to protect Mother Earth’s longevity.

The Whanganui River is 290 kilometers/180 miles long and the third longest river in the North Island of New Zealand. It is the country’s longest navigable river. It’s main source is the snow-capped Mount Tongariro (1,978 m/6,490 ft) which is part of the Tongariro volcanic centre. Other volcanos include Kakaramea, Pihanga, and Ruapehu. All near massive crater Lake Taupo. Nine tributaries feed the Whanganui and flow to its mouth in the Tasman Sea in the South Pacific Ocean.

Our incredibly beautiful drive took us along 30 miles of scenic Lake Taupo and past majestic Mount Tongariro and Mount Ruapehu, which was featured as Modor in the film Lord of the Rings. [pictured]

We drove by acres upon acres of lush, bright green pasture grazed on by sheep and cattle. The meat and diary industry are the top two exports for New Zealand and unfortunately massive polluters of all water resources, a construct imposed by colonial invaders.

We arrived in Whanganui and were greeted by Hinekaa Mako, her husband Mike Smith, and Kahuranga Kawao, Whanganui iwi and friend of our Maori guide and country host, Hinewirangi Kohu Morgan, all leaders of the local marae or tribal community meeting place. We spent the evening casually asking them questions and cooking our dinner.

Calling Forth the Ancestors: Reflections on a Ceremonial Test of Intention and Honor

The next morning we drove to the marae for our official visit with the Ngati Hau (Whanganui iwi), including Ned, the official “voice of the River” who would paddle us onto the River later in the day. We made sure to be early. The air was chilly, moist and overcast with a thick marine layer since we were right next to the ocean and the wide Whanganui River. The marine layer lasted all day and contributed to the mood of the solemn mission we were on. We sat on our tribal blankets outside the marae and looked at the safeguarded tribal waka we were going to paddle later that day.

The next morning we drove to the marae for our official visit with the Ngati Hau (Whanganui iwi), including Ned, the official “voice of the River” who would paddle us onto the River later in the day. We made sure to be early. The air was chilly, moist and overcast with a thick marine layer since we were right next to the ocean and the wide Whanganui River. The marine layer lasted all day and contributed to the mood of the solemn mission we were on. We sat on our tribal blankets outside the marae and looked at the safeguarded tribal waka we were going to paddle later that day.

As it came time for our pōwhiri (welcoming ceremony), Hine gathered us at the gates of the marae to be seen and that we were there. Customarily, we seven women were to lead the delegation into the meeting and the five men to follow behind us. We did this at the previous meeting with the Tūhoe iwi.

Suddenly, Jo and Hine noticed an ancient wero ceremony was ready to test us. A wero ceremony is traditionally a warrior sentry sent out to new visitors to gauge their intentions. Are they here to do the marae harm or do they come with goodwill? Because if the new group is deemed to be harmful, the warrior is prepared to kill them.

Quickly our entry method changed. We too must send our warrior first and Hine briefed Tom Goldtooth fast with instructions and protocol. She told Tom to take the lead and that most of all he must not break eye contact with the Māori warrior. Hine said the Māori warrior would ceremoniously challenge our Dakota/Diné warrior with traditional aggressive movements and Māori chanting, all, again, to test the intruders. She said the Māori warrior will set something down on the ground, we don’t know what, it could be a feather, a stone, anything and that Tom needed to pick it up with his peripheral vision and NOT break eye contact with the Māori warrior. (No photos were allowed during this ceremony.)

The Ngāti Hau warrior was intensely muscled with overall body moko/tattoos. He wore a traditional beaded breech cloth. He was fierce in voice and aggressive in spear movement. He challenged us and was clearly in defense mode. He was alone except for one woman also in traditional dress, who had his back. He performed the wero with expertise. The Māori warrior came close to our group with a spear and jabbed at Tom to measure our intentions. After a series of forceful ceremonial moves he came even closer and reached behind his back to pull a single fern frond from his belt. With his face maintaining fierceness and staring intently at Tom’s eyes he placed the fern on the ground at Tom’s feet. The Māori warrior moved back a few steps, never breaking eye contact with Tom.

We stood behind Tom as he faced the Māori warrior. We had his back. The Māori warrior, now standing powerfully upright with his spear, sharply screamed out in a clearly piercing way to shock and intimidate us and perform the final challenge to see what our warrior was made of. Tom naturally did what we’ve done for centuries in a war challenge. He answered back with a fiercely loud war whoop. It was spine chilling and matched the tenor of the Māori warrior’s aggressive vocal test. He retreated having deemed us of good intentions and honoring the prowess of our warrior. We were allowed to enter the marae.

We learned later that day that the Ngāti Hau had never been challenged like that before and they found it completely appropriate and honoring of our hosts, in fact, invigorating. We were all standing strong behind Tom, our Dakota/Diné warrior. I have to say my emotions during this event are noteworthy. I was overcome with with an intense sense of peripheral power, something that emanated outside of our little band of a dozen warriors. I wanted to sit down and sob, not from fear, grief or joy but from a profound sense of energy, more energy than the 12 of us could generate.

We learned later that the Māori wero challenge ceremony called to the ancestors of both the Ngāti Hau and our ancestors to be present. The Ngāti Hau’s ancestors were there on their homeland. But they also summoned our warrior ancestors, to have our backs. This is what I felt, sheer power and energy and our ancestral presence. My cheii (Navajo maternal grandfather) was there, I felt it.

We were allowed to enter the marae and walked as a group to sit in chairs facing the Ngāti Hau. Tom held the fern and did not put it down as Hine instructed him.

Kahuranga Kawao wearing a feathered cloak sang a mournful song. A young man gave a prayer in Māori. Our Māori hosts sitting with us in our group nodded at times and once said, “oh that’s beautiful.” Mike Smith welcomed us with a short speech.

It was our turn. We women rose and Casey Camp Horinek led us with a Ponca water song in honor of the Whanganui River. I anointed myself with corn pollen carried here by Deon Ben from the Navajo Nation. I placed some in my mouth and on my forehead and offered it to the sky as is our Navajo/Diné practice of blessing the event. Tom then placed our gifts to the Ngāti Hau in the center of the court and gave a speech in Dakota and then repeated it in English. Deon did the same in Navajo/Diné.

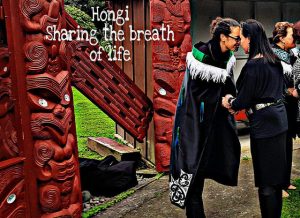

After our official welcome into the marae, the Ngāti Hau leaders lined up in front of the lodge and we went one by one to greet each individual with a hongi, meaning to share breath, the customary Māori way of pressing your forehead and nose against someone else’s to look into their spirit and share breath. And if a stranger, to see what’s inside the other’s soul.

After our official welcome into the marae, the Ngāti Hau leaders lined up in front of the lodge and we went one by one to greet each individual with a hongi, meaning to share breath, the customary Māori way of pressing your forehead and nose against someone else’s to look into their spirit and share breath. And if a stranger, to see what’s inside the other’s soul.

We were asked to come inside the lodge. We removed our shoes and took seats on the floor. We went around the room and individually introduced ourselves and where we were from. Those who spoke their Native language did so and then repeated in English. We each talked about our unique perspectives of growing up in our different tribes. We talked about the general mission we all wanted to accomplish and that was to unite in a common cause of protecting Mother Earth.

Next it was time for tea, we walked outside to another building, removed our shoes again to enter and enjoyed hot beverages and pastries. Hine broke out in song and looking at her and the red patterned trim around the cornices of the room nudged me into remembering that I had seen that scene the night before in a dream.

It was announced that since we were at the window of the river, it was time to go talk to the river. We walked a few hundred feet to the tribe’s stone boat ramp, the waka was there waiting and perched on the shore for us. We were met by Ned, the steward of the tribal waka and Keeper of the River, a huge responsibility and honor. He gave us some brief instructions before we asked to walk down and bless the river, to talk to her.

Casey and Pennie pulled out their tobacco and made offerings in the river. Casey sang the Ponca Water Song for the river and anointed each of the women with the river water on the top of our heads. We knelt and put our hands in the water collectively so the Whanganui could feel our intentions. Casey ended her song crouching over the water as she began to weep, blending her tears into the river. Casey, Pennie and Shannon collected water into little jars to take home to mix with our waters. Volcanic signature pumice stones, large and small, floated by.

Casey and Pennie pulled out their tobacco and made offerings in the river. Casey sang the Ponca Water Song for the river and anointed each of the women with the river water on the top of our heads. We knelt and put our hands in the water collectively so the Whanganui could feel our intentions. Casey ended her song crouching over the water as she began to weep, blending her tears into the river. Casey, Pennie and Shannon collected water into little jars to take home to mix with our waters. Volcanic signature pumice stones, large and small, floated by.

It was time to row. We were given life jackets, oars and more instructions on how to paddle properly.  Ned lined us up on the ramp and placed us as a matter of size in the boat to best distribute that weight. We sat two by two. Ned stood on the stern and was the Kaiwhakatere (coxswain), calling and guiding us to row in unison. We paddled upstream several hundreds of feet and then paused to talk and contemplate our day.

Ned lined us up on the ramp and placed us as a matter of size in the boat to best distribute that weight. We sat two by two. Ned stood on the stern and was the Kaiwhakatere (coxswain), calling and guiding us to row in unison. We paddled upstream several hundreds of feet and then paused to talk and contemplate our day.

We turned around to float back down the river, that was a lot easier than paddling upstream. We got wet with the misty air but also from the paddling of the water. It was hard work but invigorating and emotionally rewarding.

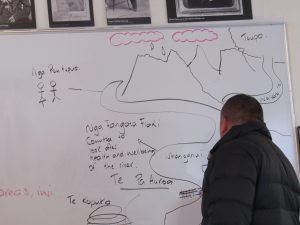

We walked back to the marae and had a delicious lunch and lovely conversations. Our afternoon meetings consisted of Ned and others explaining about the history of the river, it’s sources and how important it is to their tribe as a source of income and food, in particular harvesting eel. Ned also explained the agreement using a visual representation of this as a spiritual practice.

We walked back to the marae and had a delicious lunch and lovely conversations. Our afternoon meetings consisted of Ned and others explaining about the history of the river, it’s sources and how important it is to their tribe as a source of income and food, in particular harvesting eel. Ned also explained the agreement using a visual representation of this as a spiritual practice.

Hine and Jo carved large gourds while we listened to the speakers.

We had a visit with the former mayor, Annette Maine of Whanganui. She fought on behalf of the Ngāti Hau to gain and maintain their river rights. Annie recounted as a young girl that she was never taught about Māori history in school. As an adult she found out the truth and worked on behalf of the Whanganui Iwi. In a stunning gesture, Jo gave up her greenstone necklace so it could be gifted to the mayor to thank her for talking with us.

We had a visit with the former mayor, Annette Maine of Whanganui. She fought on behalf of the Ngāti Hau to gain and maintain their river rights. Annie recounted as a young girl that she was never taught about Māori history in school. As an adult she found out the truth and worked on behalf of the Whanganui Iwi. In a stunning gesture, Jo gave up her greenstone necklace so it could be gifted to the mayor to thank her for talking with us.

Our day was full of discovery of cultural knowledge, emotions, energy and strength. It was another common bonding, as we experienced with the Tūhoe two days earlier. An indigenous commonality of holding Mother Earth in the utmost respect and a shared abhorrent treatment by colonizers around the world. We again understand that we must continue to shed off the colonial shackles and obvious downward spiral into environmental destruction. We can move in a positive direction if we band together as many tribes, armed with our firm beliefs, cultures and shared intent.

Movement Rights: Aligning human laws with Nature’s Laws since 2014.

Most people who are familiar with the work of Movement Rights over the last five years would be shocked to learn that it has all been done by two seasoned and committed women activists—Pennie Opal Plant and Shannon Biggs—working around a kitchen table with very little funding. Our work has been a labor of love. Movement Rights’ work offers a deep structural analysis of the role of corporations in creating and sustaining the conditions for climate chaos by using our political, economic and legal systems to create wealth for the few. Indigenous traditional ecological knowledge is the basis of the rights of nature and offers an important piece in the climate justice mosaic. Aligning human law with the laws of the natural world is our big picture focus.

We can’t do this work without you. Please donate today to support our work by clicking here:

We can’t do this work without you. Please donate today to support our work by clicking here:

Movement Rights is in the streets, in the news and in the courts, providing research and reports, convening strategic gatherings, speaking at the UN and community meetings, regulatory hearings, and more. We work with a broad spectrum of state, national and global climate allies, communities and sovereign indigenous nations. We have helped thousands of people connect the dots between the critical time we find ourselves in and the solutions that Indigenous people have always known: human activity must take place within the natural system of laws that govern life on Earth.