By Shannon Biggs and Pennie Opal Plant, Movement Rights’ Co-founders

“How do we win now?” is a question many are asking in the wake of the 2017 US Presidential inauguration and the political, social and environmental reality being written using “alternative facts” and an unraveling of rights and protections. And while for the millions of those who marched in protest—many for the first time, this democratic betrayal feels new. Not so for many marginalized communities. Marching, civil disobedience and standing bravely for rights is the lesson of movements from civil rights to Standing Rock. For many Native Americans for example, exactly who sits in the Oval Office has historically had little impact on the genocide, broken treaties and environmental racism they have endured. Despite this, Indigenous people here and around the world are often the most hopeful holders for a new way forward based on some timeless truths. Here’s what is giving us hope:

On election day, Movement Rights was a world away in every sense of the word. We were in Aotearoa—the Maori word for New Zealand—learning about some of the most powerful protections for the Earth in modern law, and with our Maori guides, immersing ourselves in the ancient culture and cosmology that informs these new laws.

In particular, we were there to examine two truly revolutionary agreements between the Maori and the Crown government that recognize mountains, national parks and watersheds are not property to be owned, but as living ancestors to whom humans bear the responsibility of care. These agreements—for Te Urewera, formerly a national park in the territory of the Tuhoe iwi (tribe); and the Whanganui River settlement in the territory of the Whanganui iwi—also come with an official apology from the Crown for historic crimes against the land and the Maori people, and redress funding for new management based on Maori cosmology, community education and cultural revitalization. These laws are deeply rooted in the ancient culture and spiritual traditions of the Maori, but as we learned, they are for everyone.

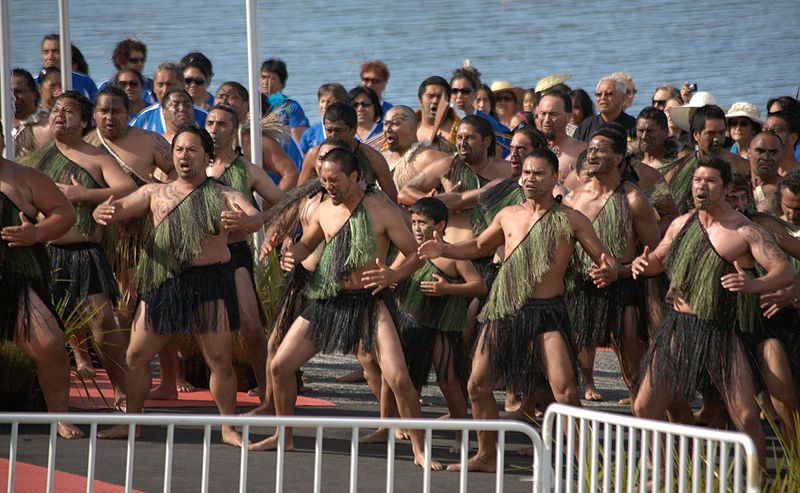

Upon landing we were greeted in a Maori way—an attention-grabbing and boisterous welcoming chant in the Auckland arrivals lounge from our partner, the Maori author-poet and activist, Hinewirangi (Hine) Kohu-Morgan. Hine was joined by her daughter, Aniwa Kohu and one of her students, Te Aho Paraha, who would travel with us as our Maori cultural guide.

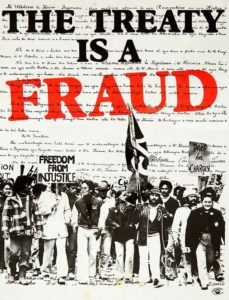

150 years of broken promises

After British colonizing forces arrived ostensibly to trade, Maori populations dwindled by 50% from European diseases and poisonings, torched crops and livestock, starvation and skirmishes with British forces.

By 1840 most Chiefs signed an agreement for coexistence—The Treaty of Waitangi. There were two versions—one in English and one in Maori—which said two very different things. Under the The English version, the Maori would become subjects of the Crown, with promises made to respect Maori practices. New Zealand would now be part of the British Empire. But property was not a concept the Maori understood. The Maori version welcomed the visitors to share the land of Aoteroa as long as they did not interfere with Maori customs, traditional and sacred practices. The Crown would violate both versions of the Treaty. It would take until now to begin the healing.

Tūhoe iwi “free” a national park

Te Urewera, has always been the homeland of the Tuhoe iwi. It is the essence of their culture, language and indentity. The land and the people are inspeperable. Once a national Park owned by the Crown, Te Urewera now has no owner. Tuhoe are known as the warrior tribe, the only iwi that never signed the Treaty of Waitangi. Today they remain fiercely independent, proud and private. Most live closely to the land in and around Te Urewera farming, ranching and hunting.

Meetings on Maori territory begin with the introduction of ancestors: the mountains you are from, the river, a greeting in the language of your heritage, where your family comes from…and then who you are. Similarly, they shared with us important ancestors whose pictures adorn the wall of their living building offices—the most sustainably advanced structure in New Zealand. We sang the Native American women’s warrior song for our Tuhoe hosts before sitting for tea and questions. These personal revelations and protocols easily shift the dynamics of those gathered. It’s difficult to hide your heart when you humbly introduce yourself by way of your great-grandmother and prayerful song.

For over two hours they graciously entertained our questions. Chief among them: how do they go from the tense relationship of colonization to brokering a deal that recognizes the spiritual wholeness of a mountain? Tamati Kruger, chief negotiator of Tuhoe’s ground-breaking Treaty settlement told us that when negotiations began, the Crown had no intention of giving away title to the park. The Crown had a “To-Do” list and a budget with which to negotiate settlements with many tribes as part of the Waiting Tribunal process.

“The Crown made a variety of suggestions over years of negotiations,” he said. “For several years we just listened. Some proposals would be [tribal] settlements from other countries.” Kirsty Luke, then a Tuhoe lawyer working on the settlement said “We’d go investigate the proposals and we’d find that when you talked directly to the affected, their communities often ended up worse off than when they began.” They recounted stories of a tribe in Alaska who negotiated for a community freezer for storing fish, and ended up losing their traditional fishing practices after only one generation of reliance on the freezer. “When we’d come back to the negotiating table with the Crown, we’d simply say, ‘no,’ and wait for the next proposal. They [the Crown] were married to ownership; first they proposed it would be tenant and landlord, and that did not suit us, or seats on the Park board,” said Tamati. Finally the Crown began to ask what was the Maori view.

Ultimately what the Tuhoe wanted was to be truly reconnected with the land that holds their cultural identity. Knowing the Crown would not cede ownership to the Tuhoe, Tamati’s team suggested that NOBODY retain ownership of the park land—rather, the land would own itself, recognized in law as a spiritual holistic entity in keeping with Maori cosmology. A new governance board of Crown and Tuhoe now ensures the rights of the ecosystem are protected. These changes also shift more than just governance of the (former) national park, it is seen as a step toward sovereignty for the Tuhoe.

The Whanganui River from mountain to sea

“This river isn’t just water and sand. It is an ancestral being with its own integrity. This river is not the river that has been contended by the crown, that exists in compartments, its bed and its waters. It’s an indivisible whole that includes iwi so this concept of legal personhood is the nearest legal approximation to the way in which we relate to our people as being inextricably entwined to it and can never be alienated from it.” Gerrard Albert, chair of Ngā Tāngata Tiaki o Whanganui.

The Whanganui Agreement, expected to pass its final legislative reading by summer 2017 will be co-managed by the Crown and Whanganui Iwi, local government and community using the lens of Maori understanding of responsibility to the sacred rights of the river. The Whanganui River, which will also have the same standing under the law as Te Urewera, includes the path of the river from Mount Tongariro to the sea, a total of 180 miles.

We met with staff and leadership of the Whanganui Trust Board, who welcomed and hosted us generously with a feast, a night together on the 100-year old meeting house, the Pungarehu Marae and a day-long meeting with negotiating lawyers, cultural and implementation staff and Whanganui elders.

We met with staff and leadership of the Whanganui Trust Board, who welcomed and hosted us generously with a feast, a night together on the 100-year old meeting house, the Pungarehu Marae and a day-long meeting with negotiating lawyers, cultural and implementation staff and Whanganui elders.

The Whanganui iwi we met with along the River were happy to share their joy, hospitality and love of the River with us that is part of their physical being as an iwi. They are known as the River People, and it is clear that the river is the source of their cultural identity. Led by our hosts from the Whanganui River Maori Trust Board, we took a boat trip down the River walked through the dense jungle alongside it, and felt the power of the land and its connection to the people.

The 150-year struggle for the rights of the Whanganui River—the longest in Maori colonial history—began to gain momentum in the 1960’s with the election of Maori officials, and a growing sovereignty movement. In 1995 the iwi began to occupy traditional land known as Pakaitore, which the Crown has made into a public park to commemorate military deaths from the 1864 Battle of Moutoa Island. For several months the Maori came, prayed and occupied Pakaitore. We met with Ken Meir, a celebrated leader of the occupation and Whanganui leader who explained that despite being evacuated from the site, something has shifted—for the iwi, the community and the Crown. “We left with the same dignity that we occupied our land, and knew that until the Crown settled our grievances we would stand to fight for our land, our river, and our people.”

In the years since, much has changed. Hayden Turoa, Program manager Te Mana o Te Awa told us: “We didn’t so much see the Crown softening to our ideas, as we hardened (into our cultural traditions).” Negotiations with the Crown have given way to the next phase of the project which includes educating and bringing non-Maori residents along the river into the Maori world view in a way that allows everyone to be connected to it spiritually, holistically.

As the former mayor of the city of Whanganui Anette Maine, has said, the agreement isn’t just for Maori, but for the whole community. “What I have seen in the document is the ability for all of us to understand how we are connected to the river and why it is so important to our lives. … there is always a bit of a feeling that as non-Maori – Maori know something that we (as Pakeha) haven’t understood and I think this is a huge opportunity for us a community to understand that story.”

What comes next

Towering over the city of Wellington, we met with Paul Beverley, lead crown negotiator for both the Whanganui and Tuhoe settlements, in an office used to sign both the agreements. We asked how the relinquishing of property has affected the mood of the Crown, businesses, regulatory agencies and the general population. He told us that there was no panic at idea of ceding property, or the idea that land and water has rights. “What has been put in place is a very forward looking framework. I think we’re going to see a springboard for this type of thing. People are already taking next steps voluntarily.”

Towering over the city of Wellington, we met with Paul Beverley, lead crown negotiator for both the Whanganui and Tuhoe settlements, in an office used to sign both the agreements. We asked how the relinquishing of property has affected the mood of the Crown, businesses, regulatory agencies and the general population. He told us that there was no panic at idea of ceding property, or the idea that land and water has rights. “What has been put in place is a very forward looking framework. I think we’re going to see a springboard for this type of thing. People are already taking next steps voluntarily.”

As Movement Rights legal director, Cabot Davis remarked, “The thing thats beautiful about it is just how differently decisions will now be made. Conflicts among people who want to ‘use’ the water or land will now have to take everyone else’s needs into account— first and foremost are the needs of the (river) system. Commerce and nature can coexist in a healthy way.”

Our journey was merely a first step for Movement Rights. Our delegation’s purpose was to examine two truly revolutionary agreements between the Maori and the Crown government that recognize mountains, national parks and watersheds are not property to be owned, but are living ancestors to whom humans bear the responsibility of care. We plan to bring a full delegation of Indigenous, environmental leaders, legal scholars and others to Aotearoa in 2017/2018 to examine these agreements, share knowledge and find ways to incorporate these victories at the tribal, community and global level. We fully believe the lessons the Maori have to teach us are globally game-changing.

Conclusion: How do we win?

Our Maori relatives remained focused on the relationships they have with sacred systems of life of which they are a part, not above nor below but within to achieve the remarkable Te Urewera and Whanganui Settlement Agreements. It is important to remember that most, if not all, civil rights in the United States only came about from the grassroots rising up to ensure that their/our rights have been recognized. From the thousands of people in the streets to ensure a Bill of Rights was attached to the US Constitution to the Abolutionists to the Suffragettes bravely asserting their rights, to Standing Rock and beyond, it has been the people rising up that ensure our rights are enshrined in the law. Now, at this critical time in history when our actions will determine the future of generations to come, it is vital that we work together to create rights-based models like the Settlement Agreements to defend, protect and restore our relationship to the sacred system of life and the natural laws that govern that system. Its time for an environmental revolution that recognizes the rights of the Earth, and our responsibilities to uphold those rights.

Movement Rights gratefully acknowledge the financial support and shared vision of the Sacred Fire Foundation and The Cultural Conservancy, for their partnership in this first step toward deepening our understanding of how to incorporate key lessons globally, and with Indigenous communities we work with. We also acknowledge our amazing partner on the ground, Hinewirangi (Hine) Kohu-Morgan, who arranged meetings, ensured we were well supported with cultural training and a driver, Te Aho Paraha who provided additional cultural knowledge and explanations on the long drive across the country.

Movement Rights depends on your support to continue our vital work for rights. To make a donation to our ongoing work with the Maori visit our website.